"Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death... Above all, I must not play at God." — Hippocratic Oath.

I've come to understand that there are two waiting lists for people who are in organ failure: The list for the organ itself and the ticking clock that leads to death.

I'm not on the right list.

I am dying of liver failure from a rare genetic type of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). I will never receive the organ that will save my life.

Nine years ago, when I was fifty-one years old, I died. I bled out in the ER due to a burst vein in my esophagus. My hemorrhage was caused by esophageal varices, a serious health condition directly related to liver disease.

Shortly after my resuscitation, I learned I had a ring of scar tissue that surrounded my liver. I was in stage 4 liver failure due to severe cirrhosis.

My cirrhosis is not caused by alcohol. I do not drink. The scarring and inflammation throughout my liver is due to a rare genetic type of NAFLD known as lean NASH, or lean nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Lean NASH is aggressive, progresses rapidly, and carries with it a higher risk of death.

Soon after my diagnosis, my doctor told me I had two years left to live—if I was lucky.

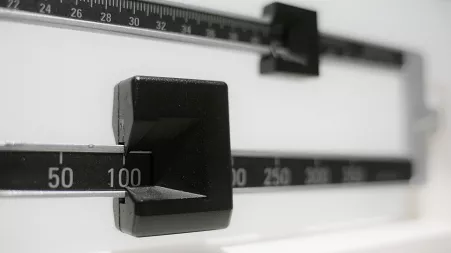

This prognosis was due to the state of my liver function measured by the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD).

The score, ranging from 6 to 40, is used to determine how quickly a person will die from liver failure without an intervention. The higher your score, the higher your priority is on the waiting list for getting a new liver.

I was told by my ICU doctor at Touro Hospital in New Orleans that my MELD score was 32. At that time, I was a prime candidate for transplant.

MELD scores are not stagnant. After my diagnosis, I strictly followed my doctor's orders, including taking all the necessary precautions and medications.

My MELD now ranges from 7 to 22, a reflection of my religious adherence to medical guidelines fighting against the inevitable failure of my liver.

Doctors at the four hospitals—Ochsner Health, Tulane Medical Center, Mayo Clinic, and USC Keck—who evaluated me for a liver transplant all approved the procedure.

The hospitals' Board of Directors ultimately rejected me because my MELD score was too low.

MELD is not always a clear indicator of a person's risk of dying of liver failure. The system has been challenged several times due to disparities, including those based on gender, ethnicity, and insurance status.

These inconsistencies emerge in how long it takes to get a referral for a transplant and the high rate of death once a person is on the waitlist. Health factors, such as ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, that increase a person's risk for death despite a low MELD score are often excluded from the scoring system.

Women naturally have a higher MELD score than men due to one of the parameters that favor males. In 2023, the scoring system was updated to MELD 3.0 to address these waitlist disparities that favored men over women.

This system has only recently taken effect. I will never receive the benefits of this change.

On the last day of 2022, USC's Transplant Center delivered my death sentence. I had two live donors with me that were known matches. After spending thousands of dollars at the center, USC sent me a letter stating that I was not eligible for a liver donor transplant.

This was my fourth and final rejection letter.

When I turn 60, my insurance will not cover the procedure.

This disease now occupies all aspects of my life. There is the pain, discomfort, and knowing I will soon die.

Then, there is the shame. Shame caused by people thinking that my disease is due to alcoholism or drug abuse. (Which, for those managing a substance use disorder, should also not be judged).

The stigma associated with liver disease leaves me and all those who share this burden with me buried in feelings of hopelessness and isolation.

Because I have been sick for so long, I now have other organs involved. I have level 3 kidney failure, heart arrhythmias, colon problems, and a host of other issues that are debilitating.

I have severe osteoporosis, another unfortunate aspect of liver disease, with its associated tooth and bone loss.

Lately, the worst has been managing hepatic encephalopathy—a brain condition that causes Alzheimer's-like symptoms because of toxins my liver can no longer clear. I am an artist, director, and scientist. My cognitive function is vital to my quality of life and ability to work.

I am a very sick woman, abandoned by those who swore to keep me from harm and injustice.

Meanwhile, in my view, the organ transplant system is crumbling under the weight of corruption, bias, and disorder.

Corruption.

From 2000 to 2004, the UCLA Medical Center gave a liver to one of Japan's most powerful gang bosses who then donated $100,000 to Westwood Hospital three months after his transplant, per Los Angeles Times reports.

In April 2024, Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center closed its doors to its liver transplant program when it discovered its lead surgeon was allegedly manipulating the government database to make patients ineligible to receive new livers.

In the same month, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center suspended its liver transplant program.

Employees at the hospital anonymously alleged to The New York Times that available organs at the center were declined on a regular basis, leaving people on the verge of death without the life-saving intervention they needed to survive.

Bias.

The organ transplant system has been challenged several times due to extensive disparities that cause needless suffering and countless deaths based on inequities.

Women, underrepresented minority populations, and people who live in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods are less likely to receive a liver transplant and more likely to die on the waitlist than a privileged, white male, according to a Johns Hopkins study.

Poorer states disproportionately lose out on liver donations to wealthier states, reported The Washington Post.

Disorder.

The poor oversight of the non-profit organization UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) which holds a monopoly on the organ transplant system has resulted in careless treatment of donated organs and a disruption of the entire system.

According to The Bridgespan Group, a non-profit consultancy, 28,000 life-saving organs could be saved yearly if not for the current transplant system breakdowns.

In July 2023, the Senate Committee on Finance held a hearing after a thorough investigation of UNOS, reporting several alarming problems.

Witnesses told horrific stories of post-transplant patients dying from contracted diseases, donor organs delivered frozen and in packages with tire marks, and thousands of organs being discarded for unknown reasons.

For now, I await my own death.

There are two life-saving treatments available to me: A liver transplant and stem cell therapy. I will not receive either of these treatments.

The stem cell therapy that could save me is not legal in the United States. And, the transplant system has failed me, as it has countless others.

I tell you my story not for pity. I want to protect you. If you test early for this disease, there are medications available that stop the progression of the disease and reverse the damage already done.

Get tested and tell others to do the same.

If it costs me my life to make a difference, I am willing to give everything I have. Every moment I have is spent researching mesenchymal stem cell therapy and spreading awareness. The organ transplant system may be failing, but I will not fail you.

I am donating my body to science.

Robyn Flanery is an award-winning director and producer, renowned for empathy-driven documentaries that inspire action and positive change, with a commitment to promoting gender equity in the film industry.

All views expressed are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.